Study of 35,000 adults finds people care significantly less about men than women in the workplace and education

Hardly anyone appears to have noticed this remarkable study of pro-women/anti-male bias, highly suggestive of gamma bias.

It’s strange how often trivial studies create an extraordinary splash of attention (e.g. the supposed benefits of ‘power posing’). In contrast, at other times huge studies of major significance land with with barely a ripple. The experimental study by Cappelen and colleagues, published last year, is a strong example of the latter.

The Cappelen et al. study included 35,000 adults in the US, and found they tended to favour women over men. The study found a tendency for people to be more accepting of males falling behind in work performance, more likely to see it as men’s own fault, and less willing to let them be helped. In most of the research questions this bias was larger from women than men, and for some research questions the bias was smaller when coming from younger participants and from Republican Party voters.

My article will briefly describe and evaluate this study, and place the study’s findings in context of relevant literature on gamma bias, intergroup biases, the gender empathy gap and related phenomena which explain gender biases.

The study and findings

The research paper by Cappelen and colleagues was published in April 2025. The study was in two parts, with 22,000 and 13,000 US participants respectively, most of them female (53%), average age 46. The key findings are outlined below.

In Part 1 of the study, a nationally representative sample of 22,000 Americans was recruited via professional survey providers, such as Ipsos. The task of the participants was to be Spectators who evaluated two workers, one man and one woman, who were doing the same job. One worker was more productive and earned a bonus, and the less productive worker got no bonus. The Spectators were asked if they wanted to redistribute the bonus, giving some of the high performer’s earnings to the low performer.

A key aspect of the experiment was that the researchers randomly assigned whether the lower performer was male or female, so that for some Spectators the low performer was male, and for other Spectators the low performer was a woman. The researchers did this to find out whether the bonus redistribution decisions of the Spectators depended on the sex of the low-productive worker.

Cappelen et al., found that around two thirds of the time, Spectators chose to redistribute earnings to the lower performer. However when the low performer was male, Spectators were less likely to redistribute the earnings than when the lower performer was female, 38.4% versus 31.1%, a 7.3% gap.

The explanations given by Spectators for their allocation choices were revealing: “a significantly higher share of [Spectators] believe that males fall behind in the choice experiment due to lack of effort than females, 53.0% versus 44.3%”, a 8.7% gap.

In Part 2 of the study, a new set of over 13,000 participants were asked how much they support government equality programs related to education and the labor market. They result was 54.2% of participants supported programmes for women, but only 42.2% supported programmes for men, a 12% gap. But an even greater gap was seen in attribution of effort: 46.7% of participants attributed male disadvantage to lack of effort compared to only 32.5% for female disadvantage, a gap of 14.2%.

Bias was greater from women

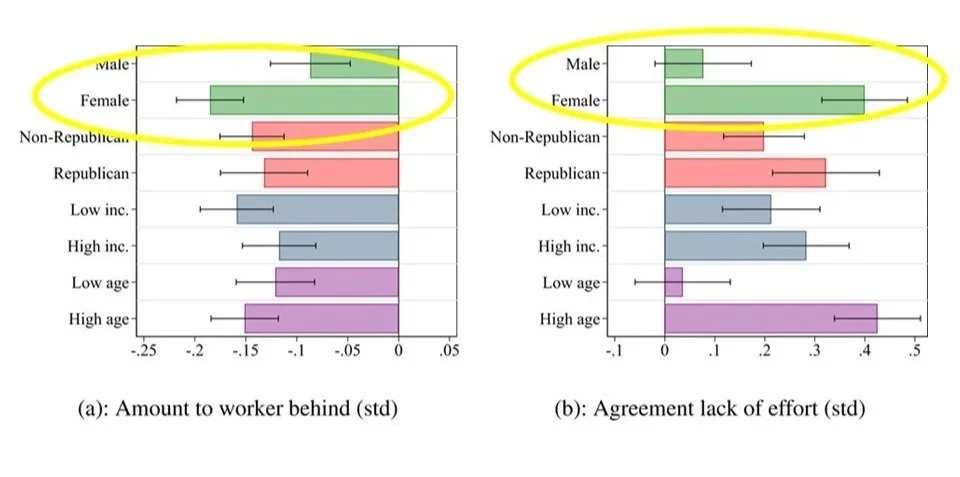

Although bias against men was shown by both men and women, another finding of the study was the bias was larger from women than from men in three out of four of their research questions. The circled section in Fig 3a (below, left) shows that both men and women in Study 1 redistributed more earnings to the lower performing worker if the lower performing worker was female rather than male, but that the effect was bigger (shown by the longer bar within the circle) when women were making the redistributions.

Figure 3

On the left, Fig 3a shows the sex difference in bias is borderline statistically significantly higher from women for bonus distribution (“amount”) (β = 0.098, p<.051; Appendix Table A.8). On the right, Fig 3b shows bias is significantly higher from women for ‘effort’ (β = -0.323, p<.01; Appendix Table A.9).

Similarly, the circled section in Fig 3b (above, right) shows that both men and women attributed low earnings to low effort more when the worker was male rather than female, but that the effect was much bigger (shown by the longer bar) when women were making the attributions.

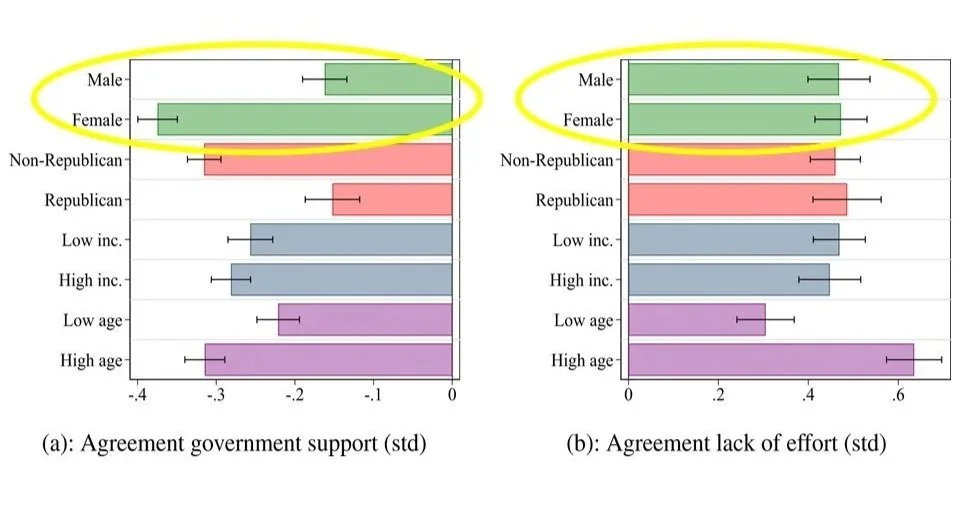

Figure 6a (below, left) shows data from Study 2, and the circled section shows women were less supportive of men than men were supportive of men, though both men and women were more supportive of women than men.

Figure 6

On the left, Fig 6a shows statistically more bias (regarding support) from women (β = 0.212, p<.01; Appendix Table A.12). On the right, Fig 6b shows no sex difference in bias regarding effort (β = -0.004, p = .960; Appendix Table A.13). (Bars show estimated effects from population-weighted linear regressions, described here).

Note that Figure 6b (above, right) shows no sex difference in attribution of effort (circled section, with bars of equal length), in contrast to the sex difference in bias seen in Figures 3a, 3b, and 6a. We could speculate that the lack of sex difference in bias here was because the question about effort related to Fig 6b was about people in general, whereas the question about effort related to Fig 3b was about the specific workers they were rating in Part 1 of the study.

Explanations for the findings

The explanation given by Cappelen et al. for the bias was “statistical fairness discrimination: People consider males falling behind to be less deserving of support than females falling behind because they are more likely to believe that males fall behind due to lack of effort.” This explanation has the merit of being derived from the response of the participants in this study (see discussion below re Table A24). However in my opinion the paper would have benefitted from considering existing theories and explanations that might explain these findings.

In the US today, ideas like such as patriarchy theory, male privilege, the ‘gender pay gap’ and ‘glass ceiling’ are widespread, and it is likely that a sample of people from this culture will reflect these attitudes to some degree. With this in mind it’s interesting to look more closely at the reasons given by Spectators for their allocations of earnings.

“Although the most common main reason for allocating pay was summed up by the researchers as ‘effort’, it would be surprising if ideas like Gender, Equality and Egalitarianism were not also prominently in the minds of some Spectators”.

Table A24 (in the appendix) shows 14 categories of reasons for allocations of pay in Study 1, and although Cappelen et al., the researchers, identify ‘effort’ as the main overall explanation, some of the other main reasons for allocation of funding are of relevance, in particular ‘Gender’, ‘Equality’, and ‘Egalitarianism’.

Table A24 gives one or two examples for each category of explanation. An example in the ‘Gender’ category was “Because in this society women have to work so much harder for what they earn.” An example of ‘Equality’ as a main reason for allocation was “Equal pay for the same job.” An example in the ‘Egalitarianism’ category was “No matter what we should all get the same pay.” So although the most common main reason for allocating pay was summed up by the researchers as ‘effort’, it would be surprising if ideas like Gender, Equality and Egalitarianism were not also prominently in the minds of some Spectators as reasons for allocations. The authors state that list of 14 categories in Table A24 is “neither comprehensive nor exhaustive”, highlighting the possibility of other dimensions to the pro-woman/anti-male bias found.

Psychological explanations for the findings

If we consider reasons like Gender rather than focusing on Effort., then other explanations for the findings become more salient. The attribution in this study of worse performance to lower effort in men, but not women, suggests a ‘fundamental attribution error’ for gender, of the kind seen in gamma bias, where male success is typically seen as privilege and male failure is seen as deserved, whereas women’s success is seen as deserved and women’s failure is seen as the result of sexism. Similarly, the concept of the gender empathy gap predicts that problems facing men are overlooked whereas problems facing women are considered a cause for serious concern. The pattern of bias is interesting too from the perspective of social identity theory, which originally predicted that people favour others who share their identity, and are biased against others who don’t share their identity; the present study reflects the phenomenon which surprised academics when it was first identified in research around 25 years ago: women favour other women, but men don’t favour other men.

Bias of this kind is implicated by the findings of various other studies too, for example, of moral typecasting, access to STEM jobs, and in health promotion. The idea that the findings are caused by a “pro-women/anti-men bias” sentiment is nothing new, and indeed this is exactly what was found in a large well-designed study a few years ago, not dissimilar to the study by Cappelen et al.

Bias related to sex, age, and party politics

The variable most associated with bias in this study was sex (being a woman), but two other variables were also linked to the bias: age (being older) and party politics (not voting for the Republican Party). Previous research supports the findings regarding politics, and gives partial support for the finding regarding age.

Regarding party politics, it is known that being left-leaning politically is strongly correlated with beliefs such as feminism and patriarchy theory. The evidence regarding age is more mixed. For example, a large international study in 2025 found younger women are more sympathetic to men: 29% of female Baby Boomers and 39% Generation Z females agreed “we have gone so far with women’s equality that we are discriminating against men”, whereas another recent study found that young women are much more negative about masculinity than are older women.

Final comments

Although this study was strong in terms of research design, it could have been improved by being more thorough in it’s interpretation of the data. For example, the authors under-explored the sex difference of the pro-women/anti-male bias, and of the three instances where there was a sex difference (shown in Figures 3a, 3b and 6a), they only commented on one instance (in Fig 6a). Also, a discussion of the findings in relation to gamma bias and other relevant psychological theories would have been welcome, though this is perhaps an understandable omission given that the background of the research term is economics rather than psychology.

The authors conclude by commenting on future efforts to understand “how statistical fairness discrimination shapes behavior and policies” and emphasised the “need to carefully examine how we relate to people who are struggling in society”. Further research is indeed needed, but I would like to caution that this topic is difficult to research. That’s partly because the biases being examined are not only to some degree unconscious, unacknowledged, and even considered a good thing, but mostly because they are so pervasive, as these views of participants in Cappelen et al. study demonstrate. Being pervasive, the bias is not just confined to participants, but some many people who can influence the research. For example, social scientists might feel this way of looking at the world is ‘social justice’ rather than a ‘bias’, thus not reasonable to question in research; funding bodies might think putting this topic under the microscope is not how their governing boards and sponsors will think grants are best allocated; ethics committees might not think it morally justifiable to ‘problematise’ this topic in research; peer reviewers might not feel comfortable to implicitly validate challenging findings by publication; and the academic and media environment might consider papers on this topic too controversial to disseminate for discussion. Although clearly this study has passed most of those hurdles, given the magnitude of the study and it’s huge social implications, it has received remarkably little attention in the 9 months since its publication.

This study is published in a culture where the term ‘gamma bias’ is almost unknown, but ideas like ‘patriarchy’ and ‘the glass ceiling’ are not only widely recognised, but considered urgent problems. Despite our culture voting for parties that enforce gender equality schemes that put men’s education and careers behind women’s, women very often want a man who earns more money and has a higher education than she does. Thus we are living in a situation that seems designed to leave everyone dissatisfied, yet this is the design that people demand.

Disclaimer: This article is for information purposes only and is not a substitute for therapy, legal advice, or other professional opinion. Never disregard such advice because of this article or anything else you have read from the Centre for Male Psychology. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of, or are endorsed by, The Centre for Male Psychology, and we cannot be held responsible for these views. Read our full disclaimer here.

Like our articles?

Click here to subscribe to our FREE newsletter and be first

to hear about news, events, and publications.

Have you got something to say?

Check out our submissions page to find out how to write for us.

.