Approaching parental alienation with compassion and common sense: An interview with counselling psychologist Dr Sue Whitcombe.

The family is, arguably, the cornerstone of society. Growing up in an happy family is a blessing, but an unhappy family might cause long-term problems. Many of the people interested in male psychology will be aware of something called ‘parental alienation’, even if it is just a vague sense of controversy around terminology. Whatever your terminological preferences, there is no doubt that the problem it describes – a child turning against one of the parents – is heartbreaking. How long this endures and how severe the mental health effects is not well researched, but is reported by alientated parents to be long-term and severe. One reason this is a male psychology topic is that, despite vocal claims to the contrary, there is evidence that fathers report being victims of this behaviour more than mothers do. Someone who has dedicated many years to focusing on the facts and rising above the controversy without ignoring it, is Dr Sue Whitcombe.

John Barry (JB): You work as a counselling psychologist with family issues. What got you interested in this topic, and what are the main challenges and rewards of the work you do?

Sue Whitcombe (SW): Happenstance! The theme of my life. I’ve never been one for life plans – any sort of planning, really. Something happens, I “have” to follow it up, it lights a fire in me, or I see some injustice and feel an urge to act. Or I see an opportunity – and I think, “that looks ok”, or “I’ll give that a go.” It certainly wasn’t my intention to work with separated families when I began my training.

Around the time I was starting my Doctorate, I developed a friendship with a man and his 10-year-old daughter; she seemed to get on well with my youngest, around the same age. He was a “non-resident parent”, who saw his daughter only on a Saturday. I began to notice some “odd” behaviours in this young girl. These piqued my curiosity – I tried to understand what might be going on for her. A year later, following a minor disagreement, she totally refused to see her dad – and was supported in this by her mum. As he tried to see her, to sort out whatever the problem was, she began what I can only call a campaign of vilification against him – saying the most horrendous things about him to her teachers, friends, on social media. Not just about him, but about his wider family, and about me. I just did not understand why.

So, faced with my lack of understanding (I detest not understanding things!), I began that process of trawling the internet to try and find some clues. That’s when I came across “Parental Alienation.” The description of the phenomenon seemed to chime with what I had observed with my friend and his daughter. Optimistically, I thought “problem identified, now let’s get it resolved …” Sadly, not.

“There was assumption that any “blame” for the relationship breakdown must lie with him, and him alone […] I also had to face up to an uncomfortable truth: if not for my first-hand experience, I would have similarly judged this man too.”

In trying to secure help for my friend, I was met with a total lack of understanding by professionals – and a lot of discrimination and judgement. There was assumption that any “blame” for the relationship breakdown must lie with him, and him alone – an experience relayed by the many fathers, mothers and grandparents I have met along the way. I also had to face up to an uncomfortable truth: if not for my first-hand experience, I would have similarly judged this man too. I became aware that my lack of understanding had probably led me, unwittingly, to make matters worse between my friend and his daughter. On reflection, I realised that this dynamic had likely been present for a number of children and families I had worked with over the years. My lack of awareness had probably led to my collusion or failure to intervene appropriately. I harboured guilt.

These were my motivations to focus my doctoral research on parental alienation and, once qualified, set up a social enterprise to work with children and families experiencing post-separation difficulties.

Sadly – the challenges far outweigh the rewards! This is not a comfortable, easy space in which to work. The main challenge has been tackling the lack of awareness. It is very difficult to seek help when you can’t attach a label to what your experience is. I say this with an ingrained disdain for labels! From a parent’s point of view, when this happens to them, they have no frame of reference, nothing to attach that experience to – to enable them to search out and seek support. And there is so much shame, and self-blame, perpetuated by a society, even friends and family, who believe you must have done something horrendous if your child doesn’t want to see you. This is changing, and I hope that I have in some small way contributed to a wider awareness and understanding of the issue.

All of this means support is not sought until very late in the day, when the harm to the child is often great and opportunities for significant change are much reduced. And when help is sought, the lack of recognition and understanding of how to effect positive change is still an issue. “Success” – a contented, well-adjusted child able to enjoy the love and care of two parents, under these conditions, is certainly not guaranteed. And we need to be honest about this.

But the rewards – when everything comes together – the joy of witnessing a child unburdened, able to give and receive love freely, to be playful and carefree with both parents, well – what can I say? Priceless …

JB: It’s quite common these days for people to change careers in later life or decide to advance their skills. You qualified as a counselling psychologist as mature student. What did you do before and why did you decide to train in this area?

SW: It’s that happenstance thing again. My first degree was in Industrial Technology & Management. As I remember it – this course was a bit of an experiment. It was accepting arts or science A levels as entry requirements, and it became apparent to me, later, they wanted as close to 50-50 male-female cohort as they could manage.

There were high expectations for me - that I would be the first in the family to go to University. But my teens were not great for me. I had poor social skills, lack of friends, intense relationships; I wasn’t coping well. I flunked my A levels - a D and an E – my offer had been B, B, C. I scrabbled around in Clearing trying to get any place that would take me away from my home town. To my surprise, my first choice Uni still offered me a place on my preferred course. My understanding now, is that there were too few female applicants, and they didn’t dare lose one!

The course content, and level of learning, was well within my capability, but I was not in a good place. I understand now, but not then, that I was “functioning” – just! I scraped by with depressive and anxiety symptoms probably for 20 years or more. I failed the final year of my degree, and had to re-sit.

When I eventually graduated, I went to work for a quite progressive independent manufacturing company. They really fostered initiative; I have fond memories of working there. Aged 26, I was appointed Managing Director of a subsidiary company manufacturing livestock trailers. I spent a lot of time with farmers and agricultural dealers talking pigs and sheep! It was wrong in so many ways. I was the proverbial square peg in a round hole. I worked so hard to try and fit, but I didn’t. I couldn’t manage people. And while I fully understood “business”, I really struggled with the very human aspects such as laying people off and disciplinary matters.

I guess this was when the real me began to peek through. I became interested in the young men who worked for me – their stories, their lives. Some were illiterate or innumerate, but hid it well. I couldn’t understand how in the 1980s we had men who couldn’t read to a basic level, or do simple calculations. That’s when I decided to retrain as a teacher.

“I developed a real interest in barriers to learning, why some children can’t engage, or why some teachers can’t engage them. I had a fondness for those lads, seen as bad – yet misunderstood. Their trauma and difficult life experiences were poorly recognised, recast as challenging, or antisocial, behaviour.”

While my children were young, I retrained as a Design Technology (DT) teacher with the Open University. To be honest, I wasn’t a whole lot better at teaching! I really struggled with wanting to “see” each of the young people I taught as individuals. When you see 200+ children a week that’s nigh on impossible. I was teaching lower set maths and DT. My classroom management was dire! But I was good at small group work, and one to one – and found a niche in working with those who had additional needs.

As time went on, I developed a real interest in barriers to learning, why some children can’t engage, or why some teachers can’t engage them. I had a fondness for those lads, seen as bad – yet misunderstood. Their trauma and difficult life experiences were poorly recognised, recast as challenging, or antisocial, behaviour. I picked up some qualifications in SEN, a Masters in Education, and started a psychology conversion course while working as a Local Authority specialist teacher for Autism Spectrum and Social and Communication Difficulties.

While studying psychology, I began my own therapy. It was life transforming. For the first time, I knew I was “good enough”, it was ok to be me, I didn’t have to please others. I came to understand that I had done the best I could as a child with the hand that was dealt to me, to cope with what had happened to me, that I wasn’t “bad” and I wasn’t responsible. I had been sexually assaulted by two trusted adults when I was around 7 or 8 years old.

So life-enhancing was that therapy, I wanted to share it with everyone. I stumbled across the Doctorate in Counselling Psychology at my local Uni. I’d never heard of Counselling Psychology – but it looked interesting. I seemed to meet the entry requirements. And I would be “Dr”! After feeling I had underachieved, and been a cock-up for much of my life, this was my chance to prove myself – not to anyone else, but to me.

In Counselling Psychology I found “me” – my home – my purpose. I loved everything about my Doctorate: the new knowledge, its application, the research. It was the most fulfilling time of my life; well - maybe a very close run with being a mum. I was 51 years old when I qualified.

JB: What advice do you have for mature students? How important is having prior life experience?

SW: I do think prior life experience enriches learning, but it has benefits for younger fellow students too. It brings a different perspective, a curiosity and sometimes a challenge to pre-conceived ideas and assumptions.

“Adopt a “can do” attitude – I want this, how can I make it happen? Take a good long look at how to overcome barriers or remove them. Check out finance options. If you don’t have level 2 or level 3 qualifications, there may be no fees”

I was brought up with life-long learning. My mum and dad left school with just a couple of O levels. I was born when they were nineteen years old, with my dad still only part way through his apprenticeship. I remember how hard he worked to improve himself through many years at night school – an HNC and management exams. I’m fairly sure he was still doing this when I was in my teens. My mum went back to college when I was in primary school – gained an ONC, couple of A levels and continued with professional studies and exams, becoming a cost and management accountant.

Too often I come across people who focus on why they can’t do something. They draw up long lists of how it is all so impossible, or not sensible or irresponsible. Adopt a “can do” attitude – I want this, how can I make it happen? Take a good long look at how to overcome barriers or remove them.

Check out finance options. If you don’t have level 2 or level 3 qualifications, there may be no fees for these. For further studying, or changing careers, check out modern apprenticeships. For degree courses, maintenance grants (non-repayable) are still available for some, and there is some non-repayable funding for social work, nursing and some allied health professional courses. Then there are loans, which only need repaying once earning a threshold income. These cover tuition fees and living costs (including childcare). Many may never begin to pay the loan back before it is written off.

Look closely at the courses that interest you – are there part-time options or distance learning? A lot of my study has been through the Open University, and my psychology conversion at Teesside University was part-time and spread over three years. To be honest, there is far greater access to a whole range of flexible learning opportunities now than there has ever been.

Studying is often viewed as a means to an end, such as a change of career. That’s fine – but there is so much more value in learning, beyond this. Acquiring a new skill, knowledge, social engagement, being challenged, developing an enquiring mind and critical analysis skills. There is increasing evidence to suggest the benefits to older adults of later life learning in physical, psychological, and social well-being, maintaining self-confidence and preventing cognitive decline.

JB: You used Q methodology in your doctorate. Is it possible to explain what Q methodology is to someone who knows nothing about research?

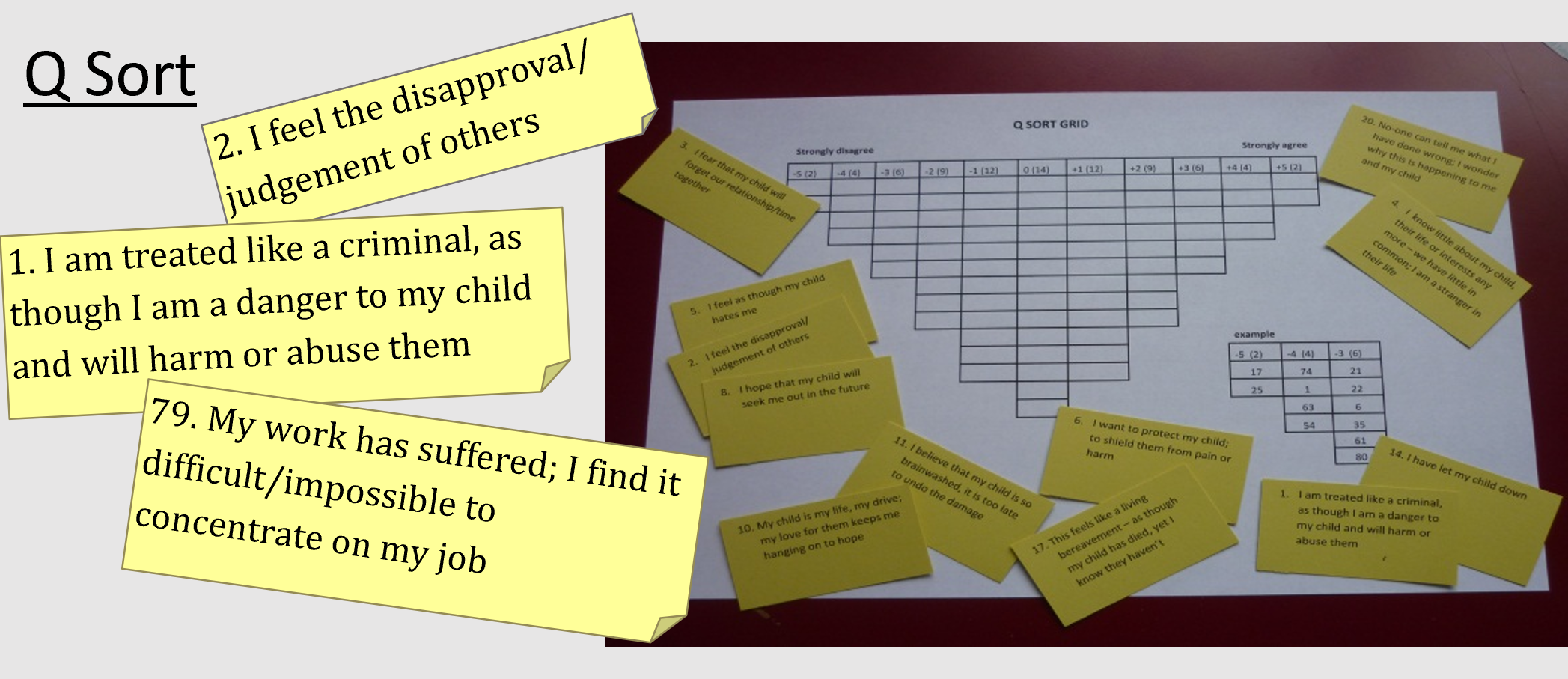

SW: I often think Q is better understood by doing it, rather than being told about it! Q is not about seeking “truth”; the results of a Q study are unlikely to be generalisable. The starting premise with Q is that each participant has a valid, yet subjective, experience of any given situation. Q seeks to understand how these experiences are constructed and whether there are commonalities, or themes, based on shared experiences.

“The constraint of the grid – one statement in one grid space – means participants are forced to consider their responses more carefully. This reduces the potential for biased responding often seen with Likert-type ranking scales.”

The initial phase is to construct a Q set – a set of statements which constitute a comprehensive range of perspectives on the subject topic. In my study this was quite difficult. At that time, there was very little published work on the experience of alienated parents. I conducted focus groups, surveyed blogs and scoured for literature. I began with 756 statements, some very similar, and whittled this down to just 80.

Participants are asked to “sort” these statements into a grid – depending on how much they agree/disagree with the statement.

The constraint of the grid – one statement in one grid space – means participants are forced to consider their responses more carefully. This reduces the potential for biased responding often seen with Likert-type ranking scales. All the completed grids are analysed, resulting in factors which represent groups of individuals who ranked the statements in the most similar way.

These factors are brought to life, interpreted with accompanying data, such as demographic information, text based additional responses and the participants’ explanations of their individual sorting process. I was quite overwhelmed by the rich, detailed stories my participants provided; it was clear they welcomed the opportunity to share their experience – and there was a sense of relief that someone wanted to listen.

Doing Q methodological research: theory, method and interpretation (2012) by Watts and Stenner is my bible for Q.

JB: You have spent over a decade interested in parental alienation, which included presenting at our Male Psychology Network conference at UCL in 2017, which was very well received. Can you explain what parental alienation is (and maybe what it isn’t)?

SW: Parental alienation refers to a child’s reluctance or refusal to see, spend time with or speak to, a good-enough, loving parent – in the absence of abuse or harmful parenting. The child’s behaviour seems disproportionate and incongruent when the entirety of that relationship is considered.

“In my experience, deliberate “brainwashing” or “coaching” is not common, though I do come across it. Rather, a child absorbs a sense that their absent parent is unsafe, or unloving, or not worthy of love, despite their own positive experience of them.”

When parents separate, their children experience a whole host of difficult thoughts and feelings. Often, they are exposed to difficult adult behaviours too. Their mum, or dad, or both may be angry, grief-stricken, jealous, hurt. They may lash out at their ex – physically – or they may seek to punish them, or exact revenge in other ways. They may sink into depression, be excessively tearful, unable to care for themselves or their child as well as they used to. They may spout venom and vitriol about their ex, or they may say nothing at all – unable to tolerate any reminder of the person who has rejected, betrayed or hurt them. To meet their own needs, they may interfere with the child’s relationship - try to stop them seeing the other parent, or communicating with them, even talking about them. They may unburden themselves of adult issues, sharing them with their child. Some of these behaviours have been labelled “alienating behaviours.”

Exposed to these behaviours, children experience a cognitive dissonance – a psychological discomfort when faced with contradictory sets of information. Their parent’s behaviour suggests that their absent mum or dad is “bad”; yet their own experience is otherwise. In my experience, deliberate “brainwashing” or “coaching” is not common, though I do come across it. Rather, a child absorbs a sense that their absent parent is unsafe, or unloving, or not worthy of love, despite their own positive experience of them.

Children, particularly younger children, do not have to have the cognitive ability to understand what they are feeling or experiencing. Rather, their discomfort manifests as anxiety behaviours around transitions – moving from the care of one parent to the other. Their anxiety is alleviated when they are removed from these situations – when they do not experience their parents in the same physical space, or do not hear their parents’ conflict, or negative commentary of the other. The child quickly learns, “if I don’t see or speak to mum or dad, I don’t have these awful feelings.”

Avoidance when feeling anxiety - any anxiety - alleviates psychological discomfort in the short term; it is rarely, if ever, a permanent solution. In this case, avoidance leads to the suppression of positive memories and the opportunity for direct experiential challenge to false, negative messages. A set of false beliefs can become embedded. The cost to the child? The loss of an important, valuable, relationship with a key attachment figure. This disruption, or severing, of their relationship with a good enough, caring parent can have a lifelong impact on a child.

The reality for children, is far more complex. It is rare to come across families where one parent actively alienates a child from the other, absent of any other factors. Our lives are dynamic, constantly changing – and very messy! Sometimes, children have experienced conflict, or abuse, in the family home before their parents eventually separate. Parents may have struggles with mental health or substance abuse; there may be financial difficulties; life events – such as redundancy, change of job, relocation, pregnancy, bereavement, infidelity. It is also common for children to have some difficulties as they navigate their normal developmental trajectory – raging hormones, friendships, relationships, questioning identity, values and beliefs. There may be a change of school, physical illnesses, bullying or additional learning needs. Then there are new partners for the adults – new parent figures for the children, new siblings. Quite often there is a succession of new partners, a constantly changing household set-up with all that entails. This is a very complex milieux in which a child has to survive, and hopefully thrive!

Far too often we seek simplistic explanations for a child’s behaviour – when the reality is often far more complex. If we fail to understand the full complexity, we will fail to suggest the most appropriate solution.

The biggest problem with the “parental alienation” label, in my opinion, is that it has become shorthand for any instance where a child is refusing to see a parent, or where a parent is preventing a child from seeing a parent. There is this concept creep: I’m not seeing my child – I am being alienated. This is unhelpful. It prevents a parent reflecting on their behaviour and feeds the acrimony and conflict.

I also believe there has been a similar concept creep with the term “domestic abuse” – now enshrined in law, not just as a pattern of behaviour, but as a single incident of psychological or emotional abuse, physical or sexual abuse, financial or economic abuse, online or digital abuse. I see the impact of domestic abuse daily. But I also routinely come across normal, occasional, difficult, relationship incidents which are cast as abusive.

Is “parental alienation” used by abusive men to counteract claims of domestic abuse? Yes, sometimes it is, though I have only come across this in a small proportion of cases. I have also come across cases where those normal, but difficult, occasional relationship incidents are promoted as domestic abuse and given as justification for preventing children spending time with their fathers.

JB: What differences exist when the alienated parent is the father rather than the mother?

SW: In my experience, there are no significant differences between men and women who identify as alienated. I hesitate to label a parent as alienated, while acknowledging they may identify themselves as such – as in my research. I guess my thinking has changed with my practice over the intervening years. That “alienated” label can encourage a sense of victimhood and prevent people reflecting, seeking solutions, making change.

One difference, however, is that mothers who have been rejected by a child often identify both as alienated, and as a victim of domestic abuse. The behaviours of their ex-partner are readily identified as abusive, often coercive and controlling. In contrast, it is unusual for a father, for men in general, to acknowledge that they may be a victim of domestic abuse. Men often modify their behaviour for years to try to avoid angering their partner. Many will have stopped seeing friends and family, had their movements closely monitored, be interrogated about who they spent time with, what they spent money on, been criticised for not being “good enough” – a lousy parent, a poor provider, the way they look, been deprived of sleep so their performance at work is affected. On separation however, the abuse is taken to a whole new level.

Threats are enacted – allegations of harm and abuse are made; they are further isolated from family & support networks; they are subject to character assassination in the community and on social media; they are forced to go to court in order to see their child. Yet this is rarely identified as domestic abuse – overt punishment and control – as it is when experienced by women. Men don’t recognise it themselves, and neither do most professionals they engage with.

JB: What is the current state of our understanding of parental alienation from a professional standpoint e.g., in academia, clinical work, legal etc? Do you think things are going in the right direction?

SW: I think I may be at odds with many academics in the field, and some practitioners, especially those from overseas. The academic field seems divided. On one side there is an increasing awareness and understanding of the overt, deliberate behaviours as being coercive controlling behaviours – as a form of post-separation IPV or family violence. This was conceptualised by Jennifer Harman and colleagues. In the UK, research into men’s experience of domestic abuse by Liz Bates and others has identified the prevalence of coercive and controlling behaviours in post separation abuse, particularly the use of threats around deprivation of the ongoing relationship with a child and threats to make allegations of harm. They have adopted the label of parental alienation for this – or it has been proposed by their research participants.

On the opposite side, there are researchers who are interested in women’s experience of domestic abuse. Here there is a focus is on post separation abuse through legal & administrative means. Many participants here are reporting that their abuser is claiming parental alienation in the family court, to deflect from allegations of perpetration of abuse (as in the “Harm Report”), and are doing so as a tool of post-separation abuse. My concern here is that both populations of participants subjectively identify as victims/survivors of abuse.

While it is important to understand personal experience, I think we seem to have lost sight of a need for fact, data, and objective truth – where is this in the research? Even in those studies which do tie the data to court cases, there remains a focus on allegations of abuse, not whether there have been findings or convictions. This is the research which needs to be undertaken, in my opinion.

We need to look at family law case data – the allegations made, whether they are found or not, the behaviours of the parents, all the contextual factors, the impact on the children, actions taken by professionals – and we need to follow this up across time. My suspicion is that the findings will be as I have stated. Children’s experiences are complex. Simplifying this down to, “Is it PA or DA?” does not serve children well. The other voice which is absent from the lived experience research, is that of the child, as a child.

With regards to the legal landscape. My experience is that judges are usually well able to recognise the harm a child is experiencing and the causes of that harm. If there is a failure, it is a failure to act quickly. I often see cases where harm was identified early on. Recommendations are made, orders are issued and there is often a stern warning to a parent to change their behaviour. However, without ongoing monitoring, there is often no change. The child continues to be subject to parental behaviours which are harmful, the child’s relationship with mum or dad is further damaged, and the case returns to court again and again. In my opinion, most of these cases should sit within public law, monitored and supervised by those with a responsibility for safeguarding and child protection.

Over the last five years, there has been a change in the instructions I receive from solicitors. Initial enquiries are now more likely to state that parental alienation has been found, or there are concerns about parental alienation. Previously, the use of “parental alienation” was uncommon; there would be reference to intractable contact disputes, implacable hostility, or inter-parental conflict. Whatever the instruction – the starting point for me is never “is this parental alienation or not?” It is always, “this child is reluctant, or refusing, to spend time with a parent – why?” If we go in with a focus on parental alienation it may obscure us from considering the fullness of the child’s experience.

Increasingly psychologists and social workers, here in the UK, seem to be better able to pick apart and formulate a child’s post separation experience – to identify the factors which influence the child’s presentation. The challenges are in recommending and undertaking interventions – what works and who can deliver it? Each child’s situation is unique; there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Interventions may include family work alongside individual work for one or more of the family members. Recommendations may have a focus on therapy or psychoeducation, or they may be more process or structurally oriented - assistance with parenting or communication, facilitating handovers, supporting family time. We have a well-qualified and experienced workforce who can conduct these individual elements – though bringing it all together and monitoring progress can often present a challenge.

Sometimes the harm a child is experiencing in the care of one parent requires them to be removed and otherwise cared for. Usually, this means a change of residence, where their other parent is deemed better able to meet their needs. Despite recent media representations, and the assertions of some researchers and women’s groups, this is not a common occurrence, in my experience. Where this takes place, there is usually recommendation for a brief, supported, settling in period where the child has no contact, or supervised contact, with the parent from which they are removed. Therapy or support for that parent to address their own difficulties and better meet their child’s needs is also usually recommended.

The biggest hurdle I see is timeliness. Requesting input from a psychologist is often very late in the day – after months or years of no contact. Relationships are severely ruptured, and the child has often experienced harm. The likelihood of successful remediation and repair in these circumstances is diminished. So, while there are practitioners who are able to deliver the work – sometimes independent social workers, sometimes psychologists, psychotherapists or systemic practitioners – there is often a reluctance to take this work on board. Who wants to work with such complexity, where the prospect of success may seem slim, and there is near certainty that one of the people you are trying to help is going to make a formal complaint about you?

JB: Why do you think that parental alienation is such a controversial issue? What can be done to encourage positive advancements?

SW: I think a large part of the problem is that this is widely publicised as a highly gendered issue. Part of the narrative is that claims of parental alienation are used by men to perpetrate domestic abuse. This isn’t my opinion, or my experience. However, the media project and perpetuate a dominant narrative which suggests men are harmful to women and children. Our press is full of stories of misogynistic, coercive, controlling, dominant men. This seems to have led to all men being looked on with suspicion, as an offender in waiting.

In contrast, women are most often portrayed as nurturing, protective, beyond suspicion. We are rarely told that mothers harm their children too – until they have perpetrated the greatest of harms as in the recent cases of Logan Mwangi, Lexi Draper and Scarlett Vaughan and these two children in Northern Ireland.

We are fed stories of children being torn from the arms of loving, nurturing mothers and forced into the arms of “abusers.” What is usually meant is “alleged abuser” – where the existence of findings or criminal convictions is not clarified. Have children been placed in the care of a parent who has findings or convictions for domestic abuse? Yes – I’m fairly sure that this has probably happened. But this is only half of the story. What we are not told, is that the mother will likely have been found to have harmed the child too. This is usually the situation in the cases I am aware of. The child’s welfare has been deemed to be best met by being placed in the care of the parent who is more able to meet their needs going forward, the parent who is least likely to cause them further harm. We need to consider all the sources of harm to which a child is exposed, whether there has been a change in parental behaviour, and the likelihood of future change.

I think we can begin to address this misrepresentation by the transparent publication of all family law judgements. This has improved – but still far too few are published to enable a comprehensive view of the cases which come to court. I do have concerns though, as we have seen to date, that there will be a promotion in the press of only those judgements which fit the dominant narrative. How often do you see a news article about children being ripped from the arms of a loving father, or, as is often the case – prevented from seeing their safe, loving father for three, five, seven years or more?

“I have a fantasy (almost certainly naïve) of working with those that “block” me […] I would love to work with them on some truly empirical research […] I wonder about heavily gendered lenses which conceptualise relationships through male power and control, when I often see women, mothers, holding the power.”

There is also the perpetual strawman argument about Richard Gardner, who re-packaged sound psychological concepts into “Parental Alienation Syndrome”, and whether he was, or was not, a paedophile apologist and anti-mother. Children’s triangulation with a parent, their alignment, psychological manipulation, role reversal was identified long before Gardner. Reich (1949) wrote about divorcing parents, "The true motive is revenge on the partner through robbing him or her of the pleasure in the child. […] The lack of any consideration of the child is expressed in the fact that the child's love for the other partner is not taken into account."

The concept of triangulation in family systems is well-established, as is its role in impacting on children’s normal development. In the 1970s Minuchin wrote of a “cross-generational coalition” while Haley described a “perverse triangle” that pits two members of a family against another. Wallerstein & Kelly (1976) wrote about the “pathological alignment” of parent and child, continuing their studies for decades. In 2001, Kelly and Johnston reformulated their multi-factorial alienated child concept.

Since the 1980s, the explosion in family breakdown has brought these psychological concepts out into the open. There has been a similar explosion in research around the issue too. These patterns were originally observed within in-tact families – but they are now more clearly visible in separated families, where, in my opinion, they are often more damaging to the child. As parents become embroiled in legal proceedings, the child is prevented from physical, and emotional, connection with a loving parent.

Picture: Two homes.

As for positive advancements? I have a fantasy (almost certainly naïve) of working with those that “block” me – those who have entrenched views around parental alienation being “pseudo-science” and a tool of abuse. I would love to work with them on some truly empirical research, considering data objectively. From my perspective, we are often talking about the same issues, but some seem unable, or willing, to see this. I wonder about heavily gendered lenses which conceptualise relationships through male power and control, when I often see women, mothers, holding the power.

JB: What are the short term and long term signs of parental alienation? Can someone be suffering from parental alienation without knowing it? Does it only occur as a result of divorce?

SW: If a child is vehemently rejecting or avoiding a parent, this is a red flag. This child is either avoiding because that parent has harmed them, hurt them, let them down – or there are other reasons, and we need to understand what they are. Any such avoidance is a defence mechanism, but what are they defending against? It may be an adaptive defence, keeping them safe from evident harm. Or, it may be a maladaptive defence, enabling them to cope while living with discomfort, distress, internal conflict, psychological abuse – harm over which they have little power to address.

This rejecting behaviour, in the absence of abuse or harm, serves the purpose of keeping mum or dad at a distance, so they do not have to deal with their complex, uncomfortable feelings. Unable to convey these feelings, children may feel pressured to give reasons for not wanting to spend time with a parent. They often report very trivial reasons such as: he can’t cook and makes us eat supermarket value food; she makes me sit up to the table and eat vegetables; his friends tried to bribe me with chocolate; she forced me to go to the park.

A child may lash out at a parent either physically or verbally. They may hit, kick or attack with objects or weapons. They may be verbally aggressive, say they hate a parent, swear at them, call them names, demean them, tell them they are useless, a waste of space. My understanding of this is that children suppress their positive feelings, their love, their need, of mum or dad. If they acknowledge their true feelings, they then have to acknowledge that they may have hurt someone they love and who loves them; they feel guilt or shame.

Sometimes there are “false” allegations of harm or abuse. Children rarely tell me that a parent has physically, or sexually, abused them. In the case records I have seen related to my work, there are relatively few reports of a child reporting physical or sexual abuse. Often, a parent will report abuse. This can be a re-interpretation of a child’s normal experience, as abusive or harmful. A child may have a bruise or a graze. Anxious, or angry, parents may question a child repeatedly, sometimes audio or video recording their questioning. They often ask leading questions, suggest “clarifications” and the questioning can very much take on the tone of an interrogation. Repeated, leading questioning can change the child’s narrative; they may begin to repeat the parent’s interpretation when describing an event. It is less common for allegations to be malicious, false claims – though these do occur.

In childhood and adolescence, the brain undergoes massive growth and structural change, before reaching maturity in early adulthood. Exposure to continued gaslighting, where a trusted parent creates a false narrative, causing a child to question their own judgment and reality, reinforced by continued avoidance, can have a substantial impact on psychological development. This can lead to false beliefs and unhelpful, or harmful, cognitive and relational functioning indicative of psychological splitting. There may be black and white thinking, idealisation & devaluation of others, inability to critically evaluate or consider alternative perspectives, and an unstable sense of self.

There is quite a bit of research by Verrocchio, Baker, Matthewson and colleagues which looks at the psychological functioning or mental health of adults who were exposed to alienating behaviours in childhood. This seems to suggest a correlation between exposure to alienating behaviours and adult symptomology, with severity of symptoms positively correlated with exposure to alienating behaviours. There are also studies which negatively correlate the use of alienating behaviours by a parent with the level of care they provide, and correlate alienating behaviours with child maltreatment. Notably, several studies also report exposure to alienating behaviours in families which were not separated albeit at a lower rate than those where there was divorce or separation. The studies are careful to point out limitations – such as the likelihood of confounding variables, the retrospective nature of the studies and the fact that nearly every adult child of separated parents reports exposure to one or more of those behaviours referred to as alienating.

Children are unlikely to identify themselves as being “alienated” or harmed, simply because of the deployed defence mechanisms – they need to believe they are safe, well-cared for. Once they reach late teens, early adulthood, many young people begin to reflect on, or question, their childhood experiences and begin to understand that the narrative they were given, may not be accurate.

As I have said, the label “parental alienation” is indiscriminately used. We can see that so-called alienating behaviours are present in in-tact families as well as separated families, and children exposed to such behaviours do not always reject a parent. Can we definitively determine that any adult symptomology or functioning is caused by alienating behaviours? I would suggest not. It may be a factor, but we know family breakdown, separation from a parent, inter-parental conflict, domestic abuse, criminality, parental mental ill-health and substance misuse all impact on a child’s development and their later adult functioning.

JB: You work as an expert witness. Can you explain what an expert witness does?

SW: I only work in family law cases, so I’ll restrict my response to this area. In England and Wales, expert evidence is only sought when it is necessary to assist the court to resolve the case. In most cases, Cafcass (Child and Family Court Advisory and Support Service) undertake some assessment and make recommendations on arrangements which they believe are in the child’s best welfare interests. Cafcass guardians and family court advisors are all social workers.

Sometimes, they feel they do not have sufficient knowledge to formulate an opinion – the knowledge required is outside their area of expertise. In these cases, an application is made to instruct an expert. This may be around testing for alcohol or drug misuse, or around the impact a parent’s mental health or psychiatric disorder has on parenting, mental capacity, forensic risk, or it may be a paediatrician or other medical professional such as when there are unexplained injuries, or complex medical needs.

My instructions are usually around the psychological functioning of a parent or child, or around family dynamics, and how these might be impacting on the child’s development, welfare and well-being. The role of any expert is to give information to the court which they would otherwise not have available – with the aim of assisting the court to make more informed recommendations with regards to child arrangements.

In all of the cases in which I have been instructed in England and Wales, I have been instructed as a Single Joint Expert (SJE). The parties agree on which psychologist they wish to instruct; if no agreement is reached – the judge rules. The situation is very different in Scotland. Here, each party can apply to instruct their own expert. Regardless of who instructs me – my overriding duty is to the court.

JB: The British Psychological Society offers some professional opportunities for those involved in expert witness work. You are registered with them as an expert witness and you sit on the BPS Expert Witness Advisory Group. How important is guidance from professional bodies and what improvements, if any, do you think could be made?

SW: I have just been involved with the updating of the British Psychological Society and Family Justice Council joint Guidance on the Use of Psychologists as Expert Witnesses in the Family Courts in England and Wales . I also contributed to the more generic guidelines relating to all expert witness psychologists. I suppose I sit at one end of the opinion range – I firmly believe that there should be regulation of all who give expert evidence in child and family cases. Where so much takes place behind closed doors, where there is a very evident power differential between the instructed expert and the subjects of the assessment and where such weight is often given to expert testimony – it is essential, in my opinion, that there is some scrutiny, oversight and a disciplinary process. We are working with very vulnerable people, and our recommendations can have a significant impact on lives. We should not take this lightly and they should have a right to raise concerns. If an expert is not subject to regulation – there is nowhere to raise concerns.

The BPS/FJC Guidance is quite generic, mindful that psychologists in differing areas of practice, or from different psychology domains, employ a range of methods to arrive at a formulation and recommendations. Psychologists are also instructed on a range of issues (as above). I would like to see some agreed protocols on what should be included in family assessments where there are concerns around conflict, domestic abuse, undue influence, ruptured parent-child relationships and emotional and psychological abuse. I feel there is much room for improvement.

“Sometimes, there is a light bulb moment. I can visibly see when someone “gets it” and it dawns on them that they have seen this in their work, but probably misinterpreted it. I had a similar awakening myself when I began reading about parental alienation.”

Besides the issues with non-regulated experts, my experience is that there is insufficient consideration given to the Annex of Practice Direction 25B. There is a requirement here for the expert’s area of competence to be appropriate to the issues, for this to be evidenced in their CV and for the expert to have been active in the area of work or practice. This is not always the case and brings the recommendations made by some experts into question. I hasten to add, this is my personal opinion – I am not speaking on behalf of the BPS or the Expert Witness Advisory Group.

JB: The Guardian recently published an article entitled ‘Parental alienation and the unregulated experts shattering children’s lives’. Can you share your thoughts on this? Did you think it was a fair representation of the issues raised?

SW: The Guardian/Observer have written quite a few articles on parental alienation recently! I wrote a blog about my thoughts and I think my responses to your other questions cover much of what I feel. I do agree with much that is written in this particular article, less so some of the others. Perhaps it would be helpful to point out where I disagree, or where I find the article to be somewhat one-sided?

I have seen assessments by court appointed experts who are not regulated, and cases where there is a clear conflict of interest in terms of stipulating specific intervention packages from the same practitioner, or a connected party. This is very much the exception in my experience. We cannot know how prevalent the instruction of non-regulated experts is. However, the vast majority of reports I have seen are by HCPC registered psychologists who are recommending evidence-based or evidence-informed interventions.

I find it baffling when I read outrage at a court’s order to protect a child from harm by a parent (which has been found by the court), by removing them for a short period of time. This is normal practice in public law proceedings – the first step is to protect the child. These orders often come on the back of a lengthy period where that parent has disrupted the child’s relationship with their other, safe, parent, often for years; no-one is shouting about this. Where is the outrage? In my experience it is far more common for a parent, unilaterally, often in defiance of a court order, to disrupt their child’s relationship with a non-abusive, good-enough parent for months, or years, than it is for the court to order a brief cessation in contact between a child and a parent who has been found to have caused them harm.

Dr Barnett expresses her opinion that parents found to have harmed their child, may be held to ransom – “forced” to engage with therapy if they wish to see their child. Parents who have been found to have perpetrated domestic abuse are also in a similar position. They are prevented from seeing their child until they have successfully completed a Domestic Abuse Perpetrators Program, ordered by the court, even where the evidence base is lacking for such programs. I have yet to hear any sympathy expressed for these parents. Why is there sympathy for some parents who harm, but not others?

As for the comments about mothers whose behaviour has been found to be harmful reporting loss of their home and life savings as well as their children. This is tragic. However, I have seen this more often with fathers - where there were no findings of harm or abuse. The passage of time and continual disruption of their relationship with their child has resulted in them walking away, for fear of causing their child distress, or the court making a no contact order, because it cannot see a way forward.

Some people suggest that there is a down-playing of domestic abuse. I am aware that this has been a feature in some cases, but it isn’t usually evident in the cases in which I have been instructed. I usually see a thorough exploration of any allegations of abuse or violence, certainly in more recent cases. In the majority of cases there has been a Finding of Fact hearing, though I would suggest this is often too late in the day. What I have noticed, is that fathers’ experience of domestic abuse, prior and post separation, is not readily identified.

JB: When discussing your work, what sort of feedback do you generally get? Do you get different reactions from those in different professionals e.g. psychologists compared to legal professionals, or women compared to men?

SW: I lived with chronic anxiety until well into my forties, and I could never stand up and speak to an audience. So it is always a surprise to me when I receive positive feedback – which is very much the norm. When speaking to professionals – whether social workers, psychologists, therapists, legal practitioners, or those working in education or health – they can usually identify children, adults or families they have worked with where the patterns of behaviour or dynamics I am speaking about are evident. Sometimes, there is a light bulb moment. I can visibly see when someone “gets it” and it dawns on them that they have seen this in their work, but probably misinterpreted it. I had a similar awakening myself when I began reading about parental alienation.

The only exception I recall was when I was contracted to deliver some training. Some domestic abuse services, and their staff, lobbied the training provider to cancel the training. The provider resisted, and some of the domestic abuse practitioners attended. I think they found it challenging, more so because all the other attendees seemed to readily grasp the learning and gave examples of their experience and practice. I hope they took away some valuable learning.

“many professionals seem to interpret the evidence “most convicted child sex offenders are men”, as “children are more at risk from their father than their mother”.”

When I speak to those who are grieving for their lost relationship – there is a huge sense of being understood; there is sadness, but gratitude too. From time to time, I speak to a more general audience, such as at a more general conference or at my doctoral graduation where I was asked to give a speech. On every occasion, at least one person has approached me afterwards, telling me they have experienced this, or they know someone who has. The first time I presented at a general conference, back in 2013, a young woman came up to me and said, “Thank you. That happened to me as a child, I didn’t know it had a name. Now I understand.”

I haven’t noticed any difference between how men and women respond to me.

JB: What is the most surprising thing you have discovered in your line of work? And if there is one thing you would want people to learn about, what would it be?

SW: I managed to live for nearly 50 years largely ignorant of the sex-based ideology and bias which seems to reign supreme in the field of family breakdown, domestic abuse and child safeguarding. To be clear – this isn’t something that dominates decisions in court, in my experience. However, it seems to be a cornerstone of much practice and policy development. Ideology and sex-based assumptions seem to trump, or displace, empirical evidence and individual case analysis.

As an example, many professionals seem to interpret the evidence “most convicted child sex offenders are men”, as “children are more at risk from their father than their mother”. I have rarely heard any concern expressed about young children sleeping with their mother, showering or bathing with their mother, mother’s wiping children’s bottoms or applying prescribed medication to intimate areas, or mother’s taking their young boys to women’s public toilets. But change the sex … Unfortunately, I have seen all of these put forward as suggesting a father has sexually abused a child – as reasons for stopping contact while investigations are undertaken. I regularly challenge professionals to flip the sex – and reflect on how their analysis and recommendation changes.

I don’t particularly want people to learn anything, but rather to tap into the knowledge they already have! There is sound empirical evidence of the social, emotional and cognitive development in children and young people. This so often seems to be forgotten when considering a child’s behaviour and presentation when caught between their parents, post-separation.

Why may a child be anxious in meeting a parent they haven’t seen for six months or a year? Yes, there is a possibility they may be fearful of them – or they may worry about disappointing them; or fear upsetting or betraying their other parent; or they may be experiencing guilt or shame about something they have done. This anxiety is normal. The professional response is then framed as: it will cause this six year old child harm if they are forced to see their (safe) parent. Where is the understanding that avoidance is not a solution to such anxiety? Where is the understanding of the importance of maintaining a child’s relationship with an attachment figure? Where is the understanding that this child will internalise unhelpful, or false, beliefs about their parent and the subsequent harm this will likely cause? I am not easily angered – but this!

JB: Do you have any new projects on the horizon you would like to tell us about?

SW: My cancer diagnosis four years ago, the whole Covid thing and becoming a granny – well it has changed my perspective quite a bit. I sold my house last year and now spend much of my time in my campervan - spending time with family and friends or just enjoying the peace, the calm, solitude – I love this freedom. I enjoy my work, but I am cautious about committing to anything long-term. I take on one legal case at a time, or work therapeutically with one family at a time; I continue to offer short-term, brief therapy, supervision and consultation.

I am focussing more on research, writing and knowledge sharing. I am currently doing a secondary analysis of my doctoral research data. I would love to undertake some collaborative research projects. My colleagues and I have so much invaluable experience which would add to the data around a child’s experience of family separation and the family court process. I am mindful of the need for robust ethics and protocols; this is particularly important to me. With this in mind, I would welcome opportunities to partner with colleagues in academia.

I’m also looking forward to researching and writing on a wider range of topics – particularly around male and female cancers, sex-bias in training and practice, aging alone, alternative lifestyles in later life, sex – the pleasurable sort, not the X Y chromosome sort (though that interests me too!). The fact is – so much interests me. I’m open to offers!

JB: Is there anything else you would like to cover that hasn’t been here?

SW: Yes – loads! But at the risk of sending the reader to sleep – I’d best shut up for now!

Final thoughts

The controversy over the term ‘parental alienation’ seems contrived, like a distraction technique designed to prevent people from recognising a particular type of human suffering because it does not fit the accepted narrative about family breakdown. In these circumstances, it is important that there are psychologists like Dr Sue Whitcombe who are dedicated to seeing the facts and helping these people, when they would be otherwise invisible and overlooked. The profession – indeed the world – needs more people who approach life with a combination of compassion with common sense, like Sue Whitcombe does.

Biography

Sue is a counselling psychologist working with separated families. Her ethos is to practise with compassion and creativity, while incorporating sound psychological theory & evidence in her work. Sue is seeking that elusive balance – appreciating life as an itinerant, campervan-dwelling granny while sharing her knowledge & experience to improve the lives of children and families. Sue is living well with vulval cancer.

Scroll down to join the discussion

Disclaimer: This article is for information purposes only and is not a substitute for therapy, legal advice, or other professional opinion. Never disregard such advice because of this article or anything else you have read from the Centre for Male Psychology. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of, or are endorsed by, The Centre for Male Psychology, and we cannot be held responsible for these views. Read our full disclaimer here.

Like our articles?

Click here to subscribe to our FREE newsletter and be first

to hear about news, events, and publications.

Have you got something to say?

Check out our submissions page to find out how to write for us.

.